|

| Murder on Hood Canal |

|

| Gothic and Historic |

|

| Tacoma WA. Murder |

Island in the Stream

. . . Your Dream

“Ineffectual,”

“inept,” “a constant failure,” these are just a few ways Ernest Hemingway

described his brother, Leicester. So

being the less-brilliant, younger brother of a world-renown author, what could

Leicester do to become famous in his own right?

Well, he could work

hard and become president of a

foreign country—a country that he created on a platform in the Caribbean Sea off the island of Jamaica, a

wacky pursuit and therefore sure to inspire others.

On July 4, 1964, Leicester Hemingway introduced the

world to New Atlantis

It’s

hard to know how serious Leicester was about his enterprise, but perhaps very

serious. He not only waited until three

years after his famous brother’s death before launching the kingdom, he also

used his own money to create it, money that came from the proceeds of his book, My Brother, Ernest Hemingway.

Approximately six

miles off Jamaica’s coast, in international waters, Leicester found a place

where the ocean floor, normally about 1,000 feet below sea level, was only

fifty feet down. “Anything we build there is legally called ‘an artificial

island,’” Leicester said.

First he put

down a foundation made of used steel, iron, and bamboo cables weighted down with

a ship’s anchor, a railroad axle, and steel wheels, an old Ford motor block, and

other scrap metal. To this he attached

an eight-by-thirty foot bamboo log platform.

He claimed half of the structure for New Atlantis and half for the

United States government, based on the U. S. Guano Island Act of 1856. In the 1850s, guano (bird poop) was a

valuable fertilizer, and Western nations were busy claiming unoccupied areas

having guano deposits. The act

authorized United States citizens to take possession on behalf of the

government of “any unoccupied island, rock or key on which

deposits were found.”

New

Atlantis’s first citizens were Leicester Hemingway, his wife, Doris, and their

daughters Anne, aged seven, and Hilary, aged three. Eventually, the citizenship grew to seven

with Leicester as president. In an ironic

but classy touch, a British subject named Lady Pamela Bird, who held dual

citizenship, became vice president. Thus, New Atlantis had its own Lady Bird.

As president,

Leicester drew up a constitution based on that of the United States but with

one line taken from the Swiss constitution which prohibited gambling.

A constitutional provision let honorary

citizens be elected president with no oath of office required.

Leicester

created an official currency comprised of a fish hook, carob bean, shark’s

tooth, and other items. He called it the

New Atlantis scruple. “The scruple was

chosen as a unit of currency,” he explained, “because the more scruples a man

has, the less inclined he is to be antisocial.”

His raft island national flag, sewn by Doris,

was a blue square with a gold triangle in the middle and a blue circle in the

middle of that. She made at least four

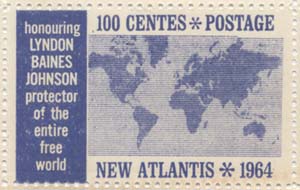

flags because storms and thieves frequently left the flagpole empty. And finally, Leicester issued five different

denominations of postage stamps. They

honored the provisional government of the Dominican Republic, the United States

4th Infantry, Winston Churchill, Herbert Humphrey, and Lyndon B.

Johnson. President

Johnson sent Leicester a letter addressed to Leicester Hemingway, Acting President, and Republic of New

Atlantis thanking his fellow president for some New Atlantis first-issue

stamps. Since it came from the president and

went through the United States postal system, it inadvertently gave the

fledgling republic approbation.

was a blue square with a gold triangle in the middle and a blue circle in the

middle of that. She made at least four

flags because storms and thieves frequently left the flagpole empty. And finally, Leicester issued five different

denominations of postage stamps. They

honored the provisional government of the Dominican Republic, the United States

4th Infantry, Winston Churchill, Herbert Humphrey, and Lyndon B.

Johnson. President

Johnson sent Leicester a letter addressed to Leicester Hemingway, Acting President, and Republic of New

Atlantis thanking his fellow president for some New Atlantis first-issue

stamps. Since it came from the president and

went through the United States postal system, it inadvertently gave the

fledgling republic approbation.

Had it not been

for storms which repeatedly took out the platform, Leicester would have enlarged

it to 100 yards wide and half-a mile long.

His future plans included a lighthouse, a shortwave radio station, a customs

house, and, of course, a post office. In

the end, he quit rebuilding and turned all the country’s documentation over to

the University of Texas at Austin.

The

purpose of New Atlantis was never clear. Leicester explained, once, that it was to

house the headquarters of the International Marine Research Society, an

organization he founded. The society’s

mission was to raise funds for marine research, and to build a scientifically-valuable aquarium in Jamaica. A possible

side benefit of the raft island was that it could possibly help protect the Jamaican

fishing industry. But then Leicester

also said he founded New Atlantis mostly to have fun and “make

dough”—presumably from the stamps.

After

the demise of New Atlantis, Leicester tried to found another island

nation—Tierra del Mar. This time, four

State Department officials explained to him, in no uncertain terms, that

“attempts at creating this (new) island would be viewed by the United States

government as a highly undesirable development, adverse to our national

interest, particularly as it might encourage an archipelagic claim,” i.e. serve

as a springboard for annexation of one of the nearby Bahaman Islands.

Private

islands and platform island nations have a long history. When George H. W. Bush was president, his

friend, Dean Kamen, inventor of the Segway, bought North Dumpling Island. Kamen referred to it as the Kingdom of North

Dumpling and to himself as Lord Dumpling. North

Dumpling is a two-acre “pirate island” in Fisher’s Island Sound off the coasts

of both New York and Connecticut. It

had a lighthouse and a replica of Stonehenge.

Kamen created his own constitution, flag, national anthem, and navy (a

single amphibious vehicle). Its currency

was in increments of Pi. Ben Cohen and

Jerry Greenfield of Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream served as joint Ministers of

Ice Cream. When Kamen was refused

permission to build a wind turbine, he joked that though he had signed a

non-aggression pact with President Bush, he would secede from the Union. At some point, however, he installed a Bergey

10KW turbine on an 80-foot, self-supporting tower that he stacked in place

using a gin-pole and winch system.

While

North Dumpling is a real island, it has nothing on Spiral Island, a “floating

artificial island first built in a lagoon near Puerto Aventuras in southern

Mexico.”

In

1998, British expatriate Reishe Sowa moved to the area along the Caribbean

coast and began picking up empty, discarded plastic bottles, left-over pieces

of wood from construction sites, and bags of leaves. The 250,000 bottles he gathered and filled

with sand became the flotation for a bamboo and plywood base on which he built

a two-story house, complete with a solar oven and self-composting toilet. Mangrove trees and other tropical vegetation he

planted on it gave the platform a real island feel and appearance. Sowa’s pets—eight cats and one dog as of

January 2006—gave it a homey feel.

Of

course what Sowa built technically isn’t an island. “Not even the president is allowed his own

island in Mexico,” he said. “I have an

eco space creating ship. I can move it,

after all.”

Nature

could also move it. After a 2005

hurricane took Spiral Island out, Sowa rebuilt what is now a tourist attraction

near Cancun.

It’s

not hard to have a quasi-island either on land or water. The International Marine Floating Structures

company has been building floating homes for twenty-five years. They have contractors throughout Canada, the

United States, Europe, and Central America.

Or for actual terra firma,

consider someplace rural, such as Nevada’s The Republic of Molossia. It’s been around for over thirty years old.

SOURCES:

This started from a pre-Google

article in Smithsonian magazine. Google micro nations and it’s all there.